In the year 1943 Germany was under pressure on all fronts, even on the so-called home front. Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Air Force, was determined to earn a place in history. He wanted to prove that a nation, namely Germany, could be forced to surrender by blanket-bombing its cities.

In the territory of the German Reich the Luftwaffe was defending itself with its back to the wall. By day it had to take on the American 8th Air Force (USAAF) which was becoming increasingly stronger, both in quality and quantity, and was as yet concentrating more on industrial targets. By night the British Air Force, following directives from Arthur Harris and Winston Churchill, tried to kill as many German civilians as possible in order to make the pressure on Hitler’s regime intolerable. Between 24th July 1943 and 3rd August 1943, when the Americans were already involved, 31,647 people (some sources even quote 40,000 civilian casualties) were killed in Hamburg alone in a series of nightly bombing raids by the British Air Force and smaller daytime incursions by the 8th USAAF.

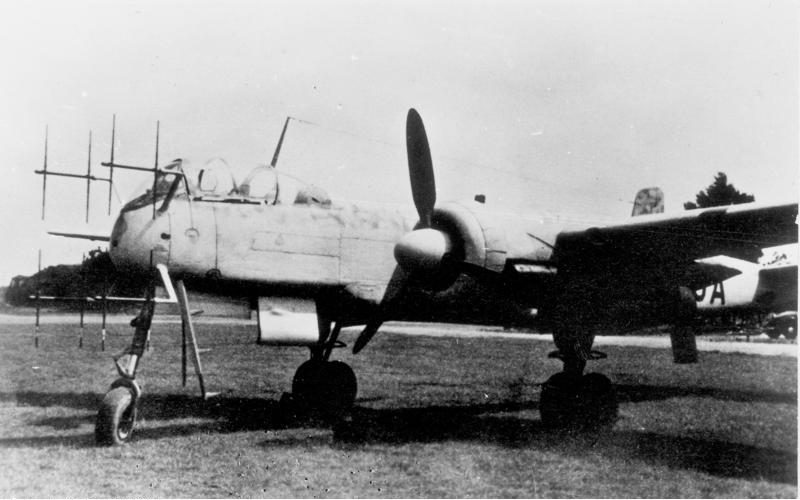

The German night fighter units relied largely on the tried and tested, though already quite old, Messerschmitt Bf 110 variants as well as the Junkers Ju 88, which were reconstructed to function as night fighters. The latter still possessed development potential, whereas the Messerschmitt night fighters by then had only a very limited capacity for design improvement. The Luftwaffe urgently needed a modern night fighter.

Heinkel had developed a technologically advanced, fast, heavily armed night fighter in the Heinkel He 219 Uhu (“eagle owl“) which proved itself to be on a par even with the British Mosquito, although only in the A-6 variant, which was drastically lightened by reducing its fire power and was only produced on a small scale, specifically to combat the Mosquito. It had a maximum speed of 404 mph compared to the 370 mph of the Mosquito NF Mk. XVII , the 372 mph of the NF Mk. XIX, and the 407 mph maximum speed of the NF Mk. 30 which was introduced towards the end of 1944.

With its mainly wooden fuselage the small, twin-engined British reconnaissance aircraft, bomber, pathfinder and night fighter was light and therefore incredibly fast. At that point in time the Mosquito was proving to be almost uncatchable in the air. A German plane, fast enough to combat the Mosquito, was the German fighter pilots’ dream. A dream which finally came true at the end of 1944 with the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet, an aircraft which outclassed any Mosquito. Towards the end of the war only very few Me 262s were deployed as night fighters but their pilots, in their desire to get even, made a point of targeting the British Mosquitos.

The He 219 was the world’s first aircraft to be fitted with an ejection seat driven by compressed air. It was available for both crew members. The pilot and radio operator sat back to back in the glazed cockpit canopy in the nose of the fuselage where they enjoyed an excellent lookout. The aircraft also had a modern retractable nose wheel. In design terms it was a state-of-the-art fighter and the A-5 variant still boasted an impressive maximum speed of 382 mph. The configuration of the armament below the fuselage and in the wing roots also prevented the pilot from being dazzled by muzzle flash. However, under the constant pressure of the bombing attacks Generalluftzeugmeister Erhard Milch decided that the number of variants had gradually become unmanageable and so production should be restricted to those models which could be mass-produced.

What he had failed to see, though, was that productivity levels of the by no means “mass-produced“ Me 110 and Ju 88 night fighters were such that fears that the new production lines for their successor might somehow affect the production levels of the current night fighters were groundless. The fact was that replacement deliveries were totally inadequate, and the idea that mass-production was being threatened by the production of the He 219 was simply fatuous.

However, Milch’s normally sound perspective deserted him in the case of the Uhu, even though Major Werner Streib of I./NJG 1 made a desperate attempt to demonstrate the superiority of this aircraft in Venlo on 11th June 1943, when he shot down five Lancaster bombers in a single night in a prototype. When Milch heard news of this he simply replied: “That man would have achieved the same in any aircraft!“

Milch would not be budged from his mistaken position, which was justifiably considered a tragedy for German night fighting. An appropriate analogy might be the originally sceptical high-ranking members of the RAF dispensing with their outstanding Mosquito for fear of woodworm. Nevertheless, Heinkel managed to deliver 268 of these superb aircraft to the Luftwaffe, despite political interference. Relatively few in the wider scheme of things, yet they were flown and were also effectively deployed in I./NJG 1.

Instead of commissioning the production of the urgently required He 219 on a large scale, the Junkers Ju 88 was now improved and from the year 1944 it was delivered in the G-1 variant. The Ju 88 G series were wonderful aircraft and in the final variant to be deployed, the G-7b (with MW 50 boost), actually reached a speed of 389 mph. Nevertheless, the He 219 was the superior aircraft.

But even the obsolescent Messerschmitt Bf 110, which in the meantime had evolved into the G-4 variant with a maximum speed of 342 mph, remained as before remarkably successful. Many of the German night fighter aces who flew that aircraft did not wish to exchange it for a different model.

Despite their self-sacrificing commitment the Luftwaffe’s night fighter pilots, in their tried and tested Messerschmitt Bf 110, their modern Junkers Ju 88 or even in the few Heinkel He 219 night fighters, were not able to prevent the destruction of the German cities. It was, however, by no means this “moral bombing” that forced the surrender of the German Reich, but rather the painful combat yard by yard on the ground.